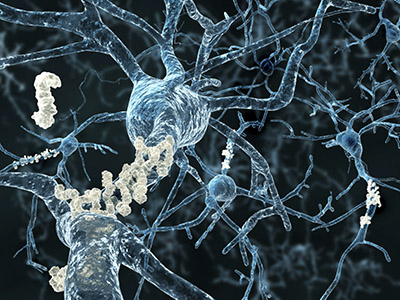

Amyloid – an abnormal protein whose accumulation in the brain is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease – starts accumulating inside neurons of people as young as 20, a much younger age than scientists ever imagined, reports a surprising new Northwestern Medicine study.

Scientists believe this is the first time amyloid accumulation has been shown in such young human brains. It’s long been known that amyloid accumulates and forms clumps of plaque outside neurons in aging adults and in Alzheimer’s.

“Discovering that amyloid begins to accumulate so early in life is unprecedented,” said lead investigator Changiz Geula, PhD, research professor in the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center. “This is very significant. We know that amyloid, when present for long periods of time, is bad for you.”

The study was published March 2 in the journal Brain.

In the study, scientists examined basal forebrain cholinergic neurons to try to understand why they are damaged early and are among the first to die in normal aging and in Alzheimer’s. These vulnerable neurons are closely involved in memory and attention.

Geula and colleagues examined these neurons from the brains of three groups of deceased individuals: 13 cognitively normal young individuals, ages 20 to 66; 16 non-demented old individuals, ages 70 to 99; and 21 individuals with Alzheimer’s, ages 60 to 95.

Scientists found amyloid molecules began accumulating inside these neurons in young adulthood and continued throughout the lifespan. Nerve cells in other areas of the brain did not show the same extent of amyloid accumulation. The amyloid molecules in these cells formed small toxic clumps, amyloid oligomers, which were present even in individuals in their 20s and other normal young individuals. The size of the clumps grew larger in older individuals and those with Alzheimer’s.

“This points to why these neurons die early,” Geula said. “The small clumps of amyloid may be a key reason. The lifelong accumulation of amyloid in these neurons likely contributes to the vulnerability of these cells to pathology in aging and loss in Alzheimer’s.”

The growing clumps likely damage and eventually kill the neurons. It’s known that when neurons are exposed to these clumps, they trigger an excess of calcium leaking into the cell, which can cause their death.

“It’s also possible that the clumps get so large, the degradation machinery in the cell can’t get rid of them, and they clog it up,” Geula said.

The clumps may also cause damage by secreting amyloid outside the cell, contributing to the formation of the large amyloid plaques found in Alzheimer’s

Geula and colleagues plan to investigate how the internal amyloid damages the neurons in future research.

Other Northwestern authors include first author Alaina Baker-Nigh, Sandra Weintraub PhD, professor in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology, Eileen Bigio, MD, Paul E. Steiner Research Professor of Pathology, William Klein, PhD, professor in Neurology and the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Shahrooz Vahedi, and Elena Goetz Davis.

Brains were obtained from the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Center Brain Bank and from pathologists from institutions throughout the United States.

This work was supported in part by a Zenith Fellows Award from the Alzheimer’s Association, and by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG014706, AG027141, AG20506 T32) of the National Institutes of Health.

If you are interested in participating in research at Northwestern University, please call the NU study line at 1-855-NU-STUDY. Or get connected by visiting https://registar-prod.nubic.northwestern.edu to sign up for Northwestern’s Research Registry.