Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered a new potential drug therapy for a rare, incurable pediatric brain tumor by targeting a genetic mutation found in children with the cancer.

By inhibiting the tumor-forming consequences of the mutation using an experimental drug called GSKJ4, they delayed tumor growth and prolonged survival in mice with pediatric brainstem glioma.

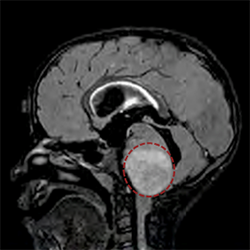

Also known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), the disease occurs when tumors form in the brainstem, which controls essential body functions such as breathing, heartbeat and motor and sensory pathways. The tumors are inoperable because of their vital location, and radiation and chemotherapy are largely ineffective. Most patients do not survive more than a year after diagnosis.

“No significant advances in the survival of DIPG patients have been made over the last few decades, and new therapeutic approaches are desperately needed,” said first author of the study Rintaro Hashizume, MD, PhD, assistant professor in Neurological Surgery and Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics..

Working with senior author C. David James, PhD, professor in Neurological Surgery, Dr. Hashizume focused on a mutation in the H3F3A gene that was recently discovered in the majority of patients with DIPG. The mutation encodes a type of protein called a histone that helps package DNA inside cells. The unexpected finding suggested the mutation had a role in DIPG development.

The mutation leads to reduced histone methylation, a process that influences gene expression. Dr. Hashizume hypothesized that pharmacologically restoring histone methylation could prevent tumor formation. He thought that GSKJ4, a small molecule inhibitor previously reported to increase methylation for immune disorder treatment, could also work for DIPG.

In the study, published in Nature Medicine, mice who received GSKJ4 treatment for 10 days survived significantly longer than those in a control group that did not receive GSKJ4.

“We are so excited by these findings, which for the first time provide evidence for pharmacologic treatment connected to a histone mutation,” Dr. Hashizume said. “Furthermore, we’ve identified a compound that may be useful for treating DIPG patients with this mutation.”

Now that the investigators know the inhibitor works against DIPG, they plan to conduct future research to see how long its effects can last with longer treatments. They also want to test the drug in combination with radiation in animal models. The ultimate goal is a clinical trial with human patients.

Fast scientific developments made this work possible

Little progress toward understanding DIPG has been made in the past for several reasons: First, there are only about 200 cases of the disease in the United States each year. In addition, it was not possible until recently to collect DIPG tissue from living patients because of the tumor’s location in the brain.

“For these reasons, there have been very few DIPG resources available to do any sort of investigation,” James said.

A few years ago, Nalin Gupta, MD, PhD, a surgeon from the University of California, San Francisco, and a collaborator on this study, developed a procedure to safely biopsy patients with DIPG, accessing tumor tissue samples of the disease unmarred by radiation and drug therapy. Dr. Hashizume modified two of these samples to establish sustainable cell lines, enabling scientists to examine the disease in this study and others.

There are still a lot of unknowns, including how GSKJ4 drug therapy might translate to humans and if the drug will be developed by pharmaceutical companies for treating cancer patients, but the scientists are optimistic.

“We’re hopeful about what these findings might do for children with this disease,” James said.

This August, Ali Shilatifard, PhD, the new chair of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, published a study in Science that investigated the same histone gene mutation, providing insights that could open the door for additional DIPG therapeutic interventions and future collaboration between Feinberg investigators.

The new study was conducted in collaboration with scientists at the University of California, San Francisco, and with support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (NCI) Brain Tumor SPORE Grant CA97257, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation, Matthew Larson Foundation, Bear Necessities Pediatric Cancer Foundation, Rally Foundation, Childhood Brain Tumor Foundation, Voices Against Brain Tumor Foundation, American Cancer Society grant IRG-97-150-13, and NIH NCI grants CA157489 and CA164746.

Dr. Hashizume and James are members of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.