Northwestern Medicine scientists discovered that genetic mutations in the KCNB1 potassium channel gene can result in severe early onset epilepsy.

They found the mutations in three children with epileptic encephalopathy, a name that refers to a group of epilepsy disorders that cause seizures and difficulties with cognitive and motor development.

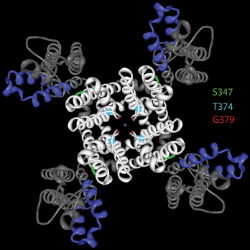

“KCNB1 potassium channels are critical for neurons to generate electrical signals and communicate with one another,” said Jennifer Kearney, PhD, associate professor in Pharmacology and a principal author of the study. “They normally dampen excitability of neurons. However, the mutations caused channel dysfunction that in turn causes excessive excitability, resulting in seizures and disrupted development.”

The findings were published in Annals of Neurology.

Many genes have been associated with epilepsy in the past. But various mutations are involved with different types of seizures in different patients.

“It’s difficult to predict which gene might be responsible in a given patient because epileptic encephalopathies are a diverse group of disorders with so many genes involved – many we haven’t discovered yet,” said Kearney.

So the team approached this study without a hypothesis that focused on a specific genetic mutation. Instead, they conducted whole exome sequencing (WES) – sequencing all genes in the human genome that encode proteins – on a child with epilepsy, as well as her unaffected sister and parents, in search of mutations that explain the underlying cause of the disorder. They found a mutation in KCNB1.

In a separate study, scientists deleted that very gene in mice and found that risk of seizure increased only slightly. Kearney’s group concluded that full-fledged epileptic encephalopathy is the result of mutations in the gene, not deletion of the gene.

The results applied to two other patients with similar dysfunction whose WES had revealed mutations in KCNB1 earlier without explanation.

“For two of the patients, the identification of KCNB1 mutations as a cause of their disorder came after a long diagnostic odyssey spanning many years,” said Kearney. “Diagnostic uncertainty is very challenging for families, so finally having a cause for the disorder is very valuable for alleviating stress and moving forward with knowledge that may improve medical management.”

Kearney collaborated with Alfred L. George Jr., MD, chair of Pharmacology, on the study.

This research was supported by Scripps Genomic Medicine, NIH-NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR025774, the Shaffer Family Foundation, the Anne and Henry Zarrow Foundation and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants U01 HG006476, R01 NS053792, R01 NS032387 and F31 083097.