A discovery by Northwestern Medicine scientists could lead to potential new treatments for breaking the cycle of tissue scarring in people with scleroderma.

Fibrosis, or scarring, is a hallmark of the disease, and progressive tightening of the skin and lungs can lead to serious organ damage and, in some cases, death.

The concept for new therapeutic options centers on findings made by Swati Bhattacharyya, PhD, research assistant professor in Medicine-Rheumatology, who identified the role that a specific protein plays in promoting fibrosis.

“Our results show how a damage-associated protein called fibronectin (FnEDA) might trigger immune responses that convert normal tissue repair into chronic fibrosis in people with scleroderma,” Bhattacharyya said. “We also found that FnEDA, which is undetectable in healthy adults, was markedly increased in the skin biopsies of patients with scleroderma.”

The study was published April 16 in Science Translational Medicine.

Scleroderma remains a disease with high mortality and no effective treatment. The factors responsible for fibrosis in scleroderma are largely unknown. Working with John Varga, MD, John and Nancy Hughes Distinguished Professor of Rheumatology and director of the Northwestern Scleroderma Program, Bhattacharyya and colleagues previously showed that innate immunity is persistently activated in scleroderma patients.

To investigate the connection between immunity and fibrosis in the disease, the scientists looked at skin biopsies of scleroderma patients to identify factors responsible for persistent scarring. They discovered that FnEDA was highly elevated.

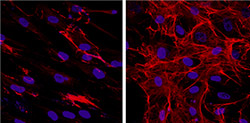

To test the theory that FnEDA was needed for the scarring to occur, Bhattacharyya used a genetically engineered mouse lacking the protein and discovered these mice did not develop skin fibrosis.

On a cellular level, FnEDA triggered an immune response in skin cells, leading to fibrosis. Moreover a small molecule which specifically blocks the cellular immune response triggered by FnEDA was able to prevent skin fibrosis in mice.

While the current study focused on scleroderma, the mechanisms uncovered might also underlie more common forms of fibrosis, such as pulmonary fibrosis and liver cirrhosis.

“This pioneering study using state of the art experimental approaches is the first to identify an innate immune pathway for scleroderma fibrosis,” Dr. Varga said. “We expect that the results will shift our thinking about the disease, and hopefully open new avenues for its treatment.”

“We have raised the possibility for developing novel therapeutic approaches,” Bhattacharyya said. “We are also developing novel small molecules to selectively block the receptor for FnEDA as a potential anti-fibrotic therapy in humans.”

The multi-disciplinary scleroderma research team included scientists at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the University of Michigan. The study was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grants AR42309 and AR057216.