Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered that scar-forming cells in scleroderma come from fat tissue within layers of the skin, a new cellular origin that could be a key to developing treatments for the incurable disease in the future.

Scleroderma, also called systemic sclerosis, is a rare autoimmune connective tissue disorder in which the skin thickens and hardens, forming scar-like buildup, a process called fibrosis. Until now, scientists have not known the mechanisms responsible for tissue fibrosis.

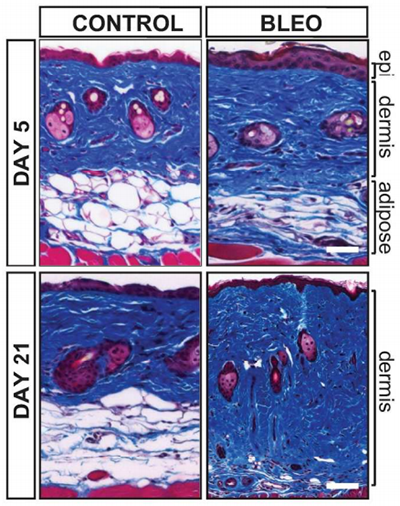

In a new study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, first author Roberta Goncalves-Marangoni, MD, PhD, research assistant professor in Medicine-Rheumatology, and colleagues examined skin biopsies from patients with scleroderma and used genetically engineered mice to show that fat within the skin called adipose tissue is an important cellular source of scarring in the disease.

“This was a surprising, but potentially important discovery,” said senior author John Varga, MD, John and Nancy Hughes Distinguished Professor of Rheumatology in Medicine-Rheumatology and Dermatology. “This is the first study to associate fat cells with fibrosis. This has implications for understanding and treating scleroderma, as well as more common forms of fibrosis such as liver cirrhosis, bone marrow fibrosis and possibly cancer.”

Fat tissue residing within the skin, unlike visceral fat stored in the abdomen, is not related to obesity. Instead, it’s thought to be involved in heat insulation, mechanical functions and energy storage. The study found that adipocytes – the cells that store energy as fat in the skin – disappear from the skin when mice develop scleroderma.

“We show that the fat cells in the skin become activated and change into scar-forming cells. They migrate into the upper layers of the skin where they cause scarring,” Dr. Varga said.

With further research, this pathway may be a target for future scleroderma therapies.

“We are now exploring ways to prevent this process and the scarring from occurring. We hope to develop drugs or use existing drugs to slow down transformation of fat cells into scar-forming cells,” said Dr. Varga, who is director of the Northwestern Scleroderma Program and a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Additional Feinberg authors involved in this study include Benjamin Korman, MD, ’12, ’14 GME, instructor in Medicine-Rheumatology, Jun Wei, PhD, research assistant professor in Medicine-Rheumatology, Warren Tourtellotte, MD, PhD, associate professor in Pathology and Neurology, and Lauren Graham, MD, PhD, resident in Dermatology. Scientists from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas and Dartmouth Medical College also participated in this work.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AR-42309, OD-010945, CA-060553 and P30AR061271 and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.