Redesigning the instructions that accompany prescribed medications increases patient comprehension, helping to ensure that drugs with serious side effects are used safely, according to a recent Northwestern Medicine study.

Investigators tested the current Medication Guide format against three alternative versions and discovered that all the new prototypes were better than the current standard. The findings were published in Medical Care.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates these Medication Guides, which contain safety information to help patients effectively use certain medications and avoid potential adverse effects. Physicians and pharmacists are required to distribute these handouts, even though they’re currently not very effective.

“We have long known, by research and common experience, that the informational material that comes stapled to your white prescription bag from the pharmacy is often confusing and of little help,” said first author Michael Wolf, PhD, ’02 MPH, professor in Medicine-General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics and Medical Social Sciences. “The FDA has sought better solutions for a tangible, understandable document that pharmacies can disseminate, particularly for drugs that pose the most serious risks to public health.”

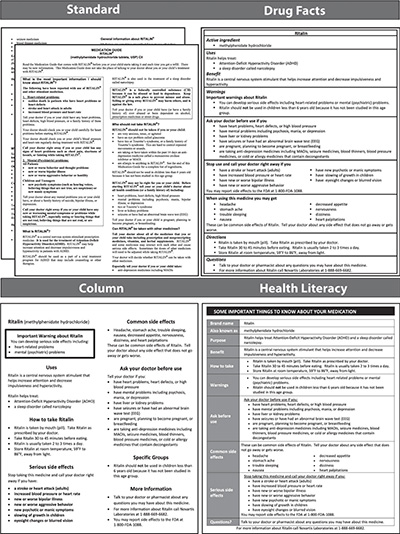

All four versions of the Guide – the three alternatives and the original one approved by the FDA – contained the same information: the drug’s name, its purpose, how to take it, important warnings, common side effects, storage instructions, resources for questions and so on. Only the organization, layout and visual appeal of the information were different.

“We specifically were interested in making a single page document that organized content in a way that made it easier for people to find what they are looking for to safely use the prescribed drug,” said Wolf, who is also a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

More than 1,000 study participants reviewed the different medication guide versions. After looking at each version, they verbally responded to questions that tested their ability to retrieve and apply the information in the Guides. The assessment was untimed and “open book” – participants could refer back to the information as needed.

“A version that followed health literacy best practices and grouped content in a simple, concise table was better than all others,” said Wolf. “Importantly, this version not only was able to improve patients’ demonstrated understanding of prescribed drugs, but it was of disproportionate benefit in aiding those with limited literacy skills.”

Wolf hopes that that the findings of this trial provide clear evidence to the FDA that the current standard for Medication Guides needs to change.

“This might provide a channel for ensuring safe use and reducing the many medication errors and adverse drug events that occur due to unintentional misuse of a drug, which costs the healthcare system billions of dollars annually,” he said.

This work was supported by a grant from Abbott Labs.