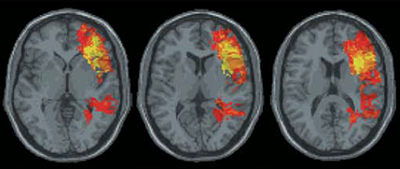

Many studies have shown that injury to gray matter, areas of the brain that contains nerve cell bodies, can cause long-lasting cognitive disability. But the role of white matter, which contains nerve cell fibers that connect groups of gray matter, has rarely been explored. In a new study, Northwestern Medicine scientists reveal that white matter loss is associated with impaired verbal abilities.

The findings, published recently in the journal Neurology, demonstrate that mapping white matter loss may indicate how much cognitive function a patient can recover after brain damage.

“This study offers a critical insight into the role of cortical disconnection as an important factor affecting cognitive recovery in brain injury patients,” said first author Irene Cristofori, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of senior author Jordan Grafman, PhD, professor in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Neurology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “The loss of white matter can prove to be a reliable or even a superior predictor of recovery, most notably for cognitive functions involving a widespread brain network, such as those required to produce words properly.”

About 13 million people in the United States and Europe live with the side effects of traumatic brain injury, particularly cognitive disabilities related to executive function – the mental skills that help a person plan and achieve goals. Impairments in this area can make it difficult to control behavior, work independently and maintain appropriate social relationships, according to Cristofori, who completed the study with fellow first author Wanting Zhong, a PhD student in the Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program (NUIN).

“Neuroplastic changes in the brain can take place immediately after damage, allowing for some restoration of the affected function, and the extent of this recovery is reflected in long-term outcomes of patients,” she said.

The investigators tested about 200 American male combat veterans – 164 who sustained penetrating brain injuries during combat and a control group of 43 who did not have a brain injury – from the Vietnam Head Injury Study, a prospective study of Vietnam veterans. All participants completed neuropsychological assessments that measured executive functions, such as verbal fluency, switching between tasks and problem solving by asking questions.

“These tasks tap into different executive function processes, including mental flexibility, planning and reasoning,” Cristofori said.

Examinations of the veterans’ brain scans showed that damage to both gray matter and white matter is related to lower performance on the tests. Loss of gray matter was more relevant in tests associated with the brain’s left frontal lobe, but this wasn’t the case everywhere.

“Producing words, which involves a broad brain network involving frontal, parietal and temporal regions, was best predicted by damage to the superior longitudinal fasciculus, a white matter tract that connects the frontal regions of the brain to more posterior areas,” Cristofori said. “Remarkably, the same observations have recently been made in patients with glioma and stroke, who also suffer damage to white matter.”

Efforts to preserve white matter could help prevent impairments to executive function in the long-term.

“For example, neurosurgeons should be more cautious when removing white matter, and helmet companies should make efforts to produce helmets that reduce shrapnel velocity and prevent the white matter damage that occurs with lesions that penetrate more deeply into the brain,” Cristofori said.

This study was supported by the National Naval Medical Center and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.