Northwestern Medicine scientists have created and transplanted an artificial ovarian system that induced puberty in mouse models. The study, published recently in Biomaterials, demonstrates a first step toward a new approach to improving fertility in childhood cancer survivors.

“We started this project because there is a lack of options for preserving or restoring fertility in cancer patients, especially those who had childhood cancer,” said first author Monica Laronda, ’11 PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Teresa Woodruff, PhD, Thomas J. Watkins Memorial Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the study’s senior author.

Chemotherapy and radiation can have damaging effects on the female reproductive system, particularly the ovaries, the endocrine organs that produce hormones essential to puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and homeostasis of systems from bones to neurons.

One experimental option for maintaining fertility involves removing a portion of the ovaries before cancer treatment and then transplanting the preserved tissue back into the patient’s remaining ovarian tissue after treatment. This strategy has led to success – 27 live births – but there is a risk that transplanting a patient’s original tissue could reintroduce cancer cells. Indeed, in this study Laronda and colleagues found that preserved ovarian tissue from three out of four patients with leukemia contained malignant cells.

“We knew that transplantation was a promising possibility, but we didn’t want to use the patient’s own tissue,” Laronda said. “So we looked into regenerative medicine technologies being used in other systems, which led us to decellularization.”

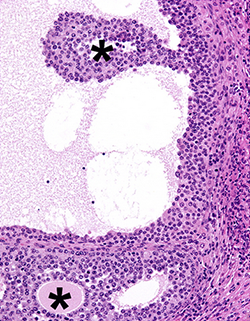

Decellularization is a process that removes the cells inside a tissue while leaving behind its structure, a scaffold-like matrix can then be recellularized with new cells. Previous studies have shown that the process can restore function to the lung, liver, kidney and heart.

In this study, the scientists first showed the steps required to effectively strip cancer cells from human and bovine ovaries (that latter of which closely resemble human ovaries). Then, in mice models, they established that the remaining scaffolds could support endocrine function once they had been reseeded with healthy cells.

“The mechanical structure of the transplant allowed the primary ovarian cells to reform and function the way they normally do in an ovary, with follicle growth and hormone production,” Laronda said.

Once transplanted into mice whose ovaries had been removed prior to puberty, the recellularized ovaries initiated puberty, providing proof-of-concept data that the process could eventually work to restore fertility in humans. The findings could apply not only to women who have survived cancer, but also to those who have lost ovarian function due to genetic conditions such as Turner’s syndrome or as a result of treatments for other diseases.

“This paper is an important first step, a way to start the conversation for this type of reproductive biology research,” Laronda said.

In ongoing research, Laronda and colleagues are investigating the differences between the extracellular matrix structure before and after chemotherapy and radiation. They’re also working to engineer a collagen-based ovarian scaffold using a 3-D printer.

This work was supported by the Watkins Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Institutes of Health grant UH3TR001207 and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant U54HD076188. The human ovarian tissue was obtained through the Oncofertility Consortium National Physicians Cooperative. Woodruff is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.