|

Northwestern University researchers are the first to design a bioactive nanomaterial that promotes the growth of new cartilage in vivo and without the use of expensive growth factors.

Minimally invasive, the therapy activates the bone marrow stem cells and produces natural cartilage. No conventional therapy can do this.

The results will be published online the week of February 1 by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Unlike bone, cartilage does not grow back, and therefore clinical strategies to regenerate this tissue are of great interest,” said Samuel I. Stupp, PhD, senior author, Board of Trustees Professor of Chemistry, Materials Science and Engineering, and Medicine, and director of the Institute for BioNanotechnology in Medicine (IBNAM).

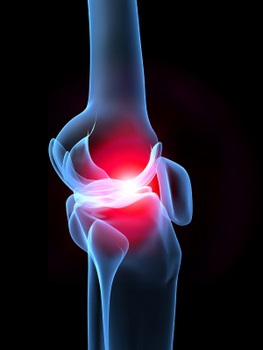

Countless people — amateur athletes, professional athletes and people whose joints have just worn out — learn this all too well when they bring their bad knees, shoulders and elbows to an orthopaedic surgeon.

Damaged cartilage can lead to joint pain and loss of physical function and eventually to osteoarthritis, a disorder with an estimated economic impact approaching $65 billion in the United States. With an aging and increasingly active population, this figure is expected to grow.

“Cartilage does not regenerate in adults. Once you are fully grown you have all the cartilage you’ll ever have,” said first author Ramille N. Shah, PhD, assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and assistant professor of materials science and engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. Shah is also a resident faculty member at the IBNAM.

Type II collagen is the major protein in articular cartilage, the smooth, white connective tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together to form joints.

“Our material of nanoscopic fibers stimulates stem cells present in bone marrow to produce cartilage containing type II collagen and repair the damaged joint,” Shah said. “A procedure called microfracture is the most common technique currently used by doctors, but it tends to produce a cartilage having predominantly type I collagen, which is more like scar tissue.”

The Northwestern gel is injected as a liquid to the area of the damaged joint, where it then self-assembles and forms a solid. This extracellular matrix, which mimics what cells usually see, binds by molecular design one of the most important growth factors for the repair and regeneration of cartilage. By keeping the growth factor concentrated and localized, the cartilage cells have the opportunity to regenerate.

Together with Nirav A. Shah, MD, a sports medicine orthopaedic surgeon and former orthopaedic resident at Northwestern, the researchers implanted their nanofiber gel in an animal model with cartilage defects.

The animals were treated with microfracture, where tiny holes are made in the bone beneath the damaged cartilage to create a new blood supply to stimulate the growth of new cartilage. The researchers tested various combinations: microfracture alone; microfracture and the nanofiber gel with growth factor added; and microfracture and the nanofiber gel without growth factor added.

They found their technique produced much better results than the microfracture procedure alone and, more importantly, found that addition of the expensive growth factor was not required to get the best results. Instead, because of the molecular design of the gel material, growth factor already present in the body is enough to regenerate cartilage.

The matrix only needed to be present for a month to produce cartilage growth. The matrix, based on self-assembling molecules known as peptide amphiphiles, biodegrades into nutrients and is replaced by natural cartilage.

The PNAS paper is titled “Supramolecular Design of Self-assembling Nanofibers for Cartilage Regeneration.” In addition to Stupp, Ramille Shah and Nirav Shah, other authors of the paper are Marc M. Del Rosario Lim, Caleb Hsieh and Gordon Nuber, all from Northwestern.

The National Institutes of Health and the company Nanotope supported the research.