Surgeon Makes Mark as Glass Artist

|

|

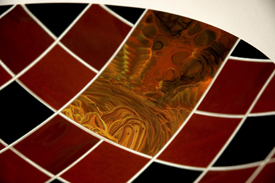

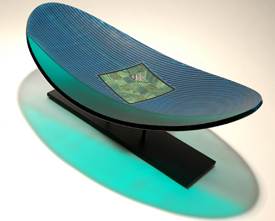

| Dr. Steve Immerman’s kilnformed glass pieces include Solar Meridian (top) and Eleuthra. |

When it comes to artistry in glass, few names are as well recognized as that of Dale Chihuly, whose colorful, fluid pieces have graced venues from the White House to the waterways of Venice. So when surgeon and artist Steven C. Immerman, MD ’77, GME ’82, of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, saw one of his own kilnformed glass pieces on display side by side with that of Chihuly at last fall’s charity auction for Pilchuk Glass School—cofounded by Chihuly—he could hardly find the words to express his joy and excitement.

Recalls Dr. Immerman, “My piece was sitting right next to a Chihuly, [Lino] Tagliapetra [a master Italian glass blower], and Dante Marioni [a well-respected American glass artist]. These are the most famous glass blowers in the world, and my piece was stuck in this cluster amongst them. It was thrilling.”

Dr. Immerman’s love affair with glass has romantic beginnings. He and his wife were on their honeymoon in Canada in 1979 when they came across an antiques store selling stained glass windows from an estate. Struck by their beauty, they bought the windows.

“Some of the windows were broken, so I had to figure out how to fix them,” says Dr. Immerman. “In the process, I learned how to make stained glass windows. During residency I had a little room set up in our apartment where I would make them. Even when I was relaxing from surgery, I liked working with my hands.”

After residency and a fellowship in surgical oncology at the McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University, he moved to Eau Claire and opened an independent, solo practice that has since grown to include two partners. In 1993 he founded Oak Leaf Medical Network, an organization of independent physicians that helps its members with activities such as marketing, contracting, and recruitment. “Around the time that I started Oak Leaf,” he says, “I realized I needed to find that creative outlet again and wanted to go back to glasswork.”

He considered glass blowing, but it didn’t seem feasible. “It requires a large studio and possibly a helper, and you couldn’t stop in the middle to answer a pager,” he explains practically. He turned instead to kilnformed glass, in which sheets and strips of glass are melted and shaped in a kiln (at 1500 degrees Fahrenheit) rather than in a furnace or with a torch.

Dr. Immerman began working in the art form in 1995, spending the first five or six years purely experimenting. To build on his repertoire of techniques, he would take a week here and there to attend classes at different locales around the country. “At first, my goal was to see how many techniques I could apply to an individual piece and still have it be attractive,” he says. “Now I’m trying to make pieces that are simple and straightforward, have some sort of message, and are beautiful.”

|

| Dr. Immerman has fond memories of his years in Chicago as a medical student, resident, and fellow at Northwestern. |

The surgeon’s Clearwater Glass Studio consists of two medium-sized, “cramped” rooms in the basement of his home and numerous tools that enable him to grind edges smooth, sandblast finishes, and remove bubbles and fingerprints that can ruin a piece. “For the first seven years I didn’t have any of these tools and had just one shot to get it right,” he says. “That period taught me a lot.”

Dr. Immerman anguishes over the design of each piece but relishes the six to eight hours spent assembling the piece by hand. “Putting it together, which is often tedious—upward of 200 strips of glass may have to be cut and fit together—is the part I enjoy most,” he relates. The piece then is fired in the kiln for 15â20 hours, cooled, and put through 3 or 4 hours of “coldworking,” which may include grinding the edges to a precise oval or sandblasting it to produce a texture. Then it may be returned to the kiln for a 20-hour cycle of “firepolishing” and sandblasted and reshaped again.

Remarks Dr. Immerman, “I often know that it’s a successful piece when I bring it upstairs to show to my wife, and she says, ‘You’re not going to sell that one, are you?’”

But his pieces do sell, typically for between $1,000 and $4,000. He’s as surprised as the next guy. “I had planned on this being a hobby that would have me puttering around in the basement making ashtrays,” he says modestly, “but all of a sudden it took off.”

Dr. Immerman’s pieces are sold at Pismo Fine Art Glass, a gallery in Colorado. “It represents some of the biggest names in glass art in the country, and I’m selling pieces,” he says in awe. “That means that people are walking into the gallery and amongst this array of absolutely fantastic glass artwork are occasionally deciding that the piece they want to walk out with is mine!”