Should I order the pizza or the pasta? According to a new Northwestern Medicine study, deciding which dish will be more rewarding involves two independent pathways in the human brain. Each pathway answers a different question about the potential outcomes: How good are they? And what are they?

The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may explain why appetite behavior can go awry for patients with disorders like frontotemporal dementia. Pathological symptoms such as hyperorality – trying to eat nonfood items – may be caused by a mismatch between these types of brain signaling.

“To make the optimal choice among several options, people must take into account information about two different aspects of the expected outcome. They need to consider the value – if it’s good or bad – and also how that value is related to the specific identity of the outcome,” said senior author Thorsten Kahnt, PhD, assistant professor in the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology.

Previous research has focused on how value is processed in the brain without regard for the identity of the outcome. But both are critical for evaluating future rewards.

“This is the first study to identify potential neural mechanisms for how the human brain processes value in conjunction with identity information,” Kahnt said.

Kahnt and first author James Howard, a postdoctoral fellow in Kahnt’s lab, exposed hungry study participants to appetizing food odors, including pizza, sautéed onions, strawberries and cupcakes.

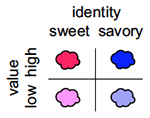

The investigators tested how information about expected future rewards is coded in the brain by having participants smell high and low values of two equally pleasant odor identities – one sweet and the other savory.

“For appetizing odors, higher intensities are more pleasant than low intensities,” Kahnt said. “We used high and low intensity versions of the two odors to manipulate values along with identity.”

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity associated with each odor stimulus, they showed that a region called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex encodes the value of a potential outcome while the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) encodes value specific to the particular identity of the outcome. In other words, the former region tells a person that pizza and pasta are both delicious, and the latter differentiates between pizza-specific and pasta-specific values.

“Value alone is not enough to make the ideal choice,” Kahnt said. “If you don’t process the identity of the reward then you cannot show appropriate behavior to obtain this outcome.”

In ongoing research, Kahnt is continuing to explore how these pathways work. Understanding how they may malfunction in patients could someday lead to targets for new therapies.

Additional authors include Jay Gottfried, MD, PhD, associate professor in Neurology, and Philippe Tobler, PhD, assistant professor at the University of Zurich.

The study was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants 1F31DC013500 and R01DC010014, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant T32NS047987 and Swiss National Science Foundation Grants PP00P1_128574, PP00P1_150739 and CRSII3_141965.