Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine has received a grant to build a microphysiologic platform to predict drug safety and effectiveness in humans better than current in vitro and animal models. The work is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Tissue Chip for Drug Screening initiative.

In a first phase of funding that began in 2012, Teresa Woodruff, PhD, Thomas J. Watkins Memorial Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and colleagues developed tissue chips – miniature models of living organ tissue on transparent microchips – to imitate the function and structure of the female reproductive tract’s five organs: the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vagina.

“We are very excited by our progress during the first two years of funding. We’ve established 3-D cultures of female reproductive tissues that respond physiologically to female sex steroids, estrogen and progesterone,” said Woodruff. “Importantly, we add them in a pattern that mimics the human menstrual cycle over 28 days. Our culture models allow us to assess changes across the cycle and in the presence of potentially disruptive compounds, such as chemotherapy and environmental toxins.”

Other teams involved in the NIH project have been simultaneously developing chips for other parts of the body – the heart, liver, blood-brain barrier and so on. In the recently announced second phase of funding, the scientists will study the organs in combination to test potential drug compounds for safety or toxicity in people.

Currently, about 80 percent of drugs fail in human clinical trials: Animal models do not always predict human response accurately, nor do isolated cell models that lack the typical complexities of human physiology.

Those complexities can vary by sex. Woodruff’s efforts to include sex-specific biology in the tissue chip project could help correct the frequent exclusion of females from clinical trials and basic science research. In drug development, this omission can lead to undetected adverse effects for female patients.

“We saw this program, paired with our expertise in female reproductive biology, as an excellent opportunity to begin alleviating some of these problems,” she said.

With their new grant, spanning three years and more than $1.5 million per year, Woodruff’s team members will combine the separate reproductive organs into an integrated system that can simulate the body’s real biological functions.

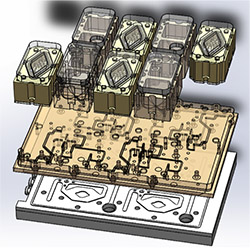

“The goal is to culture tissues on a single platform that pumps media from one tissue to the other,” said Woodruff. Her group also plans to validate their system using test compounds and to develop renewable cell sources for the reproductive tissues.

Feinberg faculty J. Julie Kim, PhD, Mary Ellen Pavone, MD, Spiro Getsios, PhD, Thomas Hope, PhD and Michael Avram, PhD, collaborated on this work, as did Joanna Burdette, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago and Jonathan Coppeta, PhD, of Draper Labs.

Woodruff is vice chair for research in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, director of the Women’s Health Research Institute and a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

The Tissue Chip for Drug Screening program is a partnership between the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the U.S. Food and Drugs Administration. The NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institute of Environmental Health and Sciences (NIEHS) and the NIH Common Fund provided additional funding for the research at Feinberg.