Northwestern Medicine scientists have found evidence of ALS-related deposits in the eyes of a patient for the first time, opening a new potential avenue for diagnosing and tracking the disease.

In ALS, proteins accumulate into clumps in the motor neurons of the brain and spinal cord. The neurons stop working and eventually die, causing muscle weakness and impaired speaking, swallowing, breathing and death.

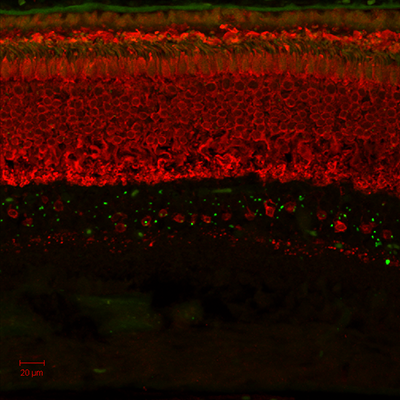

In this study, scientists studied the retina of a patient with the most common genetic form of ALS. These investigations identified the same protein deposits in the retina of the patient that are usually found in the brain in this type of ALS.

“This connection was unexpected. Beyond causing eye movement difficulties, ALS has not previously been associated with any manifestations in the eye,” said Amani Fawzi, MD, associate professor in Ophthalmology, and first author of the new study, which was published in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration.

Dr. Fawzi and Nicholas Volpe, MD, George W. and Edwina Tarry Professor and chairman of Ophthalmology, collaborated with Teepu Siddique, MD, Les Turner ALS Foundation/Herbert C. Wenske Foundation Professor in the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology and Cell and Molecular Biology on this research.

The scientists initially detected ALS-related protein deposits in the retina of an ALS mouse model. This led them to study the retina tissue from a deceased human donor. Interestingly, the deposits found in this patient explained subtle vision deficiencies indicated in the patient’s medical records.

“These deposits accumulated in a single layer of the retina, affecting a subclass of retinal neurons that we believe are particularly important in color perception and contrast sensitivity,” said Fawzi.

In this situation, the patient’s vision was only slightly impaired – likely not enough for the patient to even notice. But, importantly, noninvasive vision tests can spot these subtle abnormalities.

This opens up many opportunities for further investigation: Could physicians someday conduct an eye test to diagnose ALS earlier? Currently, an autopsy is the only way to verify the specific protein accumulations in the spinal cord and brain and thus definitively diagnose ALS.

Fawzi and the team have to answer a few other questions first.

“Do these deposits correlate with disease onset? Do they reflect disease course or prognosis? Can we detect them in the living eye using novel imaging approaches developed in our laboratories?” she said. “Optical imaging, visual function tests and detailed investigations of the nature and consequences of these deposits are still needed.”

In ongoing research, the scientists are studying a larger population of ALS patients. Using new imaging approaches, they aim to identify protein deposits and their effects in the retinas of living patients. The results, so far, have been promising.

ALS, a fatal neurodegenerative disease, affects an estimated 350,000 people worldwide, with an average survival of three to five years.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants EY-021470, NS05064, K12 EY021475, P30 EY001792 and NIA AG13854; the Illinois Eye Bank; Eleanor Wood-Prince Grants: A Project of The Woman ’s Board of Northwestern Memorial Hospital; Research to Prevent Blindness; the Les Turner ALS Foundation; Ride for Life; and the Foglia Family Foundation.