An enhanced prediction scale for large B-cell lymphoma could help physicians discern how good or bad a patient’s prognosis might be.

“We wanted to create an index in the modern era of chemotherapy that would be more powerful in separating out different subgroups, especially those patients who we expect to do poorly,” said Jane Winter, MD, professor in Medicine-Hematology/Oncology. “If it’s known that the prognosis is poor with standard treatment, a physician may opt for more aggressive therapy or enrollment in a clinical trial. Conversely, if there is a 95 percent chance someone will be alive in five years with standard treatment, there’s no need to consider alternatives.”

The International Prognostic Index (IPI), a clinical tool developed by oncologists in 1993, has been the basis for determining prognoses in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma for the past two decades.

With advancements in chemotherapy – like rituximab, now part of the current standard of care for B-cell lymphomas – Dr. Winter and first author Zheng “Frank” Zhou, MD, PhD, a third-year fellow, sought to enhance the clinical tool.

“Frank started from the ground up. Where others have tried to modify the IPI or apply it to older individuals or specific patient populations, he started with raw data and built a new analytical model,” said Dr. Winter, a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. “Our connection to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) database meant we had access to, and could review, more than 1,600 cases of large B-cell lymphoma.”

The NCCN-IPI was recently published in Blood.

The new scale differs from the IPI in that it features an eight rather than five point scale, better separating the four (low to high)risk groups. Applying the measure to 1,650 patients in the NCCN database, the index was proven to more accurately predict the five-year survival rate of individuals in both the highest- and lowest-risk categories. Dr. Zhou then validated it using an independent cohort of more than 1,000 patients from the British Columbia Cancer Agency, where it once again demonstrated enhanced discrimination for both low- and high-risk patients.

“In general, clinical factors have been the backbone of medical prognostication in large cell lymphoma for the past 25 years,” Winter said. “Even in the 21st century, with the investigation of numerous biomarkers, it continues to be the most powerful means of predicting how a patient will do.”

Because certain genetic mutations in combination with other abnormalities can signal a bad prognosis, Dr. Winter will explore whether scientists can add a biological marker to further improve the prognostic index.

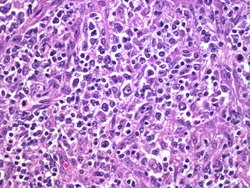

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common type of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, one of the most common cancers in the United States, infecting about 70,000 people each year.

Beyond the patient perspective, scientists rely on the IPI to make sure clinical trials remain unbiased by including patients from each prognosis category.

“We’re going to start using the NCCN-IPI and we hope that it will eventually be adopted by practicing physicians and scientists throughout the country,” Dr. Winter said. “One of our next steps will be to create an easy-to-use app where clinicians will merely need to input a set of data to receive a prognosis score.”

The project was funded by a T32 National Institutes of Health training grant to Dr. Zhou, as well as the NCCN.