Home to some of the world’s most-recognized programs of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) research, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine has for the past year been the site of a unique multi-laboratory collaboration working to uncover how this debilitating form of dementia develops.

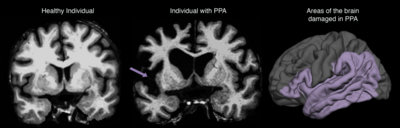

First identified in the early ’80s by M. Marsel Mesulam, MD, Ruth Dunbar Davee Professor in Neuroscience, PPA leads to a loss of language function. Other intellectual faculties such as memories and personalities tend to be maintained for many years, but patients often become mute and may eventually lose their ability to understand written and spoken words. The condition, a “cousin of Alzheimer’s disease,” often occurs in individuals in their 50s and 60s, an age that physicians don’t usually associate with neurodegenerative illnesses.

The medical school’s most recent project is a three-laboratory collaboration supported by a seed grant from the Josephine P. and John J. Louis Foundation.

“The Louis Family came to us to see if we could propose something truly unique that would lead to major progress in our understanding of PPA,” said Mesulam, director of the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center (CNADC). “We prepared an unusual proposal to combine the established PPA research programs at the CNADC and my laboratory with two world-class laboratories that had never before worked on PPA but could introduce unique synergies for collaborative research in this area.”

Mesulam will work alongside John Csernansky, MD, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and Robert Vassar, PhD, professor in cell and molecular biology in this endeavor. The investigators will focus their efforts on a specific type of PPA, characterized by abnormal accumulations of the protein TDP-43, one of three known causes of the disease.

In Mesulam’s lab, researchers will study autopsied brain specimens from patients who had the TDP-43 type of PPA in an attempt to clarify the relationship between the protein and the death of nerve cells in language centers.

These findings will be compared to what Vassar’s lab discovers in a mouse model of the disease. The overlapping areas will allow researchers to focus on those parts that are directly relevant to PPA in humans.

Csernansky’s lab is responsible for creating both behavioral and imaging processes to identify PPA-related changes in the brains of living mice so that similar approaches can be developed to detect them in humans. Since physicians can currently confirm a diagnosis of PPA only via autopsy, having processes to identify the disease while the patient is living would allow doctors to better prescribe and monitor treatment, Csernansky said.

Beyond these three core laboratories, the project will tap into Northwestern’s unique set of resources, like the CNADC Brain Bank in Chicago and the Center for Advanced Molecular Imaging (CAMI) in Evanston.

CAMI was created to drive interdisciplinary research, bridging the gap between basic science and science-based medicine, and provides researchers with access to a wide range of imaging instrumentation.

“CAMI provides a number of modalities, can image from molecule to mouse, and has partnered with experts to provide state of the art volume rendering and visualization tools on site,” said Thomas Meade, PhD, CAMI director.

Building upon the availability of the CAMI, CNADC, and the laboratories involved, the ultimate goal of the study is to find treatments that will slow or halt the progression of the disease

“I am not sure that this project could take place anywhere else in the world given the exhaustive series of experiments and amount of cross-correlated data involved,” Vassar said. “To look at human disease and mouse models from multiple angles is very important. We are still in the early stages, but by mid-winter we will have results to analyze and can begin to write a paper for publication.”

With data collection likely to be completed in December, the New Year will present an opportunity for all three laboratories to come together and evaluate results, draw conclusions, and determine the future direction of the project.