Stem Cell Promise Must be Fully Explored, Says Silverstein Lecturer Sean J. Morrison, PhD, who directs the University of Michigan Center for Stem Cell Biology, says he receives constant questions and pleas for help from people who suffer from ailments ranging from Parkinson’s disease to spinal cord injuries.

Sean J. Morrison, PhD, who directs the University of Michigan Center for Stem Cell Biology, says he receives constant questions and pleas for help from people who suffer from ailments ranging from Parkinson’s disease to spinal cord injuries.

The importance of stem cell research in helping to find cures for these and other conditions—and the tricky political crosswinds whipping around the issue—prompt Dr. Morrison to observe that he and researchers in his field battle in the “trenches,” not the ivory tower.

“You can’t stand in my shoes without feeling a sense of urgency about this,” said Dr. Morrison, who spoke October 17 at the Pancoe/ENH Life Sciences Pavilion in Evanston and October 18 at the Robert H. Lurie Medical Research Center in Chicago, as part of the Center for Genetic Medicine’s Silverstein Lecture Series.

“We have to do everything we can for those who are suffering,” he said. “One of the things that happens when science gets politicized is that the truth sometimes gets lost.”

Dr. Morrison clarified distinctions between embryonic stem cells, which can be developed into any kind of cell and can be propagated as “lines,” and tissue-specific or “adult” stem cells, which are limited both in quantity and versatility.

Tissue-specific cells are useful to researchers, Dr. Morrison said, but the argument over whether to use embryonic or adult cells is a political argument only. “If we’re really serious about curing disease, we should be using all the weapons at our disposal,” he said.

Political opponents of embryonic stem-cell research often frame the ethical question as a choice between medical research or “making babies,” Dr. Morrison said. But given the thousands of embryos routinely discarded from fertility clinics, it’s really about medical research versus creating more medical waste, he said.

“President Bush frequently presents this misinformation when he addresses this subject,” Dr. Morrison said. Noting that embryos used in research are microscopic bundles of a few hundred cells, he added, “What I’m talking about here has nothing to do with abortion.”

The federal restrictions on use of embryos that Bush signed into law in 2001, which affect most researchers since most depend on federal support, “only delay medical research,” he said. “They do not prevent a single embryo from being destroyed. That’s why proponents of this work get so frustrated.”

Dr. Morrison illustrated several scenarios in which the use of embryonic stem cells could prove vital. For example, juvenile diabetes, caused by the death of insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas, can be controlled by transplanting such cells from corpses—but not nearly enough qualified donors exist to meet the need.

Alzheimer’s disease is sometimes caused by a genetic defect that could be injected into embryonic stem cells in a petri dish, where researchers could watch how the disease progresses. “This is a kind of application that you absolutely could not get otherwise,” Dr. Morrison said. “This is why Nancy Reagan talks about the importance of stem cells.”

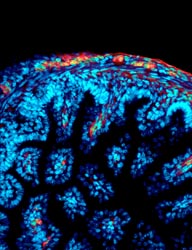

Researchers believe cancers such as leukemia, breast, colon and some brain tumors are driven by infrequently occurring stem cells that subdivide out of control, he said. If these cells could be positively identified and a method developed to target them, patients would not need to undergo traditional chemotherapy.

Researchers believe cancers such as leukemia, breast, colon and some brain tumors are driven by infrequently occurring stem cells that subdivide out of control, he said. If these cells could be positively identified and a method developed to target them, patients would not need to undergo traditional chemotherapy.

Dr. Morrison’s center will soon begin a clinical trial for a therapeutic drug called rapamycin that showed promise in research on mice. “If we kill off the cancer stem cells, we will effectively convert metatstatic cancer cells to benign cells,” he said. “This is the cool thing about stem cell research: it creates opportunities.”

University of Michigan researchers are also examining whether the overall aging of the body could be a stem cell-related disorder. As people gets older, their stem cells stop dividing as quickly and tumor-suppressing defenses ramp up, Dr. Morrison said. Research on mice has showed removing tumor suppressors reverses the effects of aging on neurons.

“This tells us that things aren’t just wearing out with age,” he said. “In fact, stem cells are actively shutting themselves down.” That allows people to become older before they get cancer, but “the bad news is, it makes us get older.”

Posted October 24, 2007